Madrid, February 2021 – On 11th February 2021, the Spanish prime minister and chairman of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) Pedro Sánchez presented Spain’s ‘Entrepreneurial Nation Strategy’ (Estrategia España Nación Emprendedora) at the Moncloa Palace in Madrid. In his speech, Sánchez promised that the related Start-up law “will […] facilitate administrative formalities, help retain and attract the necessary talent, forge greater convergence between vocational training, universities and emerging companies, and […] include tax breaks and […] investment incentives”. While at first glance, Sánchez’ announcement might sound promising, this article will explore Spain’s Entrepreneurial Nation Strategy more in-depth, weighing the prospects and risk factors involved.

A ‘Spanish Dream’ – Beyond Individualism?

As its title suggests, Spain’s Entrepreneurial Nation Strategy (Estrategia España Nación Emprendedora) aims at transforming Spain into a start-up nation by 2030 – an effort, which the country aspires to reach through a line-up of 50 ambitious measures including priority-, investment-, entrepreneurial public sector-, scalability- and talent-related measures. While the latter are all designed to attract and promote talent from across the world, they will be implemented over a 10-year period from 2021. During this period, Spain’s government also intends to work on filling apparent gaps in Spanish society such as the gender, generational, territorial and socioeconomic gap. In other words, Spain’s Entrepreneurial Nation Strategy perpetuates the assumption that giving the Spanish start-up scene a proper boost is enough to accelerate inclusive development and transform the Spanish economy as well as individual livelihoods all at once. Whereas it is certainly an inspiring imagination that diversity and inclusion will ‘trickle down’ as Spain pursues its own version of the ‘American dream’, it is also a reality that technological change adds extra hurdles to income inequality irrespective of its importance. Whether Spain’s plan will promote an individualist form of entrepreneurship or make the latter inclusive is yet an open question.

Technological Change, Innovation and Inequality

As Lucas Kitzmueller, who works for the World Bank’s Development Data Group, Harvard’s Kennedy School and IDinsight, argues, “technological change is a primary driver of increasing market income inequality” and the stronger incorporation of AI and automation into society will very likely reinforce the declining labour demand, wages and employment in middle-skilled jobs. Ironically, this comes in a time where, as the Spanish economist Juan Thomas states, “it often occurs that waiters make more money than engineers” with the tourism and services industries as well as agriculture making up for most of Spain’s GDP. In a nutshell, whereas an ‘entrepreneurial nation’ might provide highly skilled citizens with new opportunities in the Spanish labour market, it is also necessary to analyze and address how tech start-ups and AI will transform Spain’s economy for other workers.

Not everybody can be an entrepreneur, or else the Spanish government might refrain from employing the National Innovation Company (ENISA) as a judge on the innovative nature of projects under Spain’s Draft Start-up Law (Anteproyecto de Ley de fomento del ecosistema de las empresas emergentes). As Carlos Sáez, a lawyer at Trebia Abogados who has special expertise in new technologies law, argues, it is yet unclear how ENISA will define innovation. Should the organization employ a narrow definition of the latter, start-ups with similar ideas and services, for instance related to the provision of soft- and hardware (i.e. mail management), e-commerce, delivery platforms etc., might be unable to access public funding and secure any of the proposed incentives.

Visa Programme, Vocational Training and Incentives

Even, if the Spanish government aspires to attract digital and tech nomads through a new visa programme, which might maintain or raise regional and local consumption levels meanwhile vocational training will be transformed to adequately address topics related with entrepreneurship and business, the proposed start-up law will very unlikely be able to support these groups while starting up. As Mercedes Ribero argues, corporate tax reductions do not stop start-ups from losing in their early and founding phase, because it takes a while to generate revenue. However, especially in the early stages funding is needed irrespective whether start-ups aim to overall make a small or a huge societal contribution. Next to this problem, Ribero criticizes that deductions for business angels have to be returned within a few years unless the start-up is sold within this timeframe.

Even if one may argue about this, this set-up seems aimed at increasing investments at any cost with little consideration of the visions of Spanish entrepreneurs and society and their right to own this vision. The emphasis on attracting talent from all over the world underlines this point similar to the emphasis on the visa programme and on the renunciation of the foreigner’s identification number (NIE) for foreign investors who do not live in Spain. Whereas attracting and enabling foreign investment is certainly an imperative, the draft law fails to target the average start-up. Among others, this includes the interpretation that a start-up is such, which is newly created or no older than 5 years, has their registered office or permanent establishment in Spain with 60% of the workforce having an employment contract in the country and the start-up not being the result of a merger operation.

Another problematic aspect of the draft law is that it defines an acceptable business volume as amounting to less than €5 million when, according to Embroker, the average Series A reached $12.1 in the US in 2017. Whereas Europe’s start-up scene does not yet measure up with the Silicon Valley, there are plenty of start-ups which generate more than €5 million including more recently founded startups such as Zapper (2020/ €15m), Ki Insurance (2020/ €455m) and The Protein Brewery (2020/ €26m). In other words, Spain’s draft start-up law is much too competitive in terms of general criteria as it offers too little scope for large-scale innovation. In addition, it does not mirror the intention to fill societal gaps. While education about entrepreneurship is a huge pillar of Spain’s Entrepreneurial Nation Strategy, education and the monitoring of societal gaps (i.e. gender gap) will only be effective as long as investment and incentives are accessible.

Spain’s Economy, the Entrepreneurial Nation Strategy and the ‘Spanish Dream’

As Thomas remarks, at the current moment, Spain’s economic failures are all apparent. First, the current Spanish government has withdrawn from its responsibility to take inflation seriously while the European Central Bank (ECB) keeps purchasing the government’s bonds with interest rates remaining close to zero. The latter does not only uphold a vicious cycle which could lead to bankruptcy at any given moment, but directly points at another issue with the government’s take on unemployment. Rather than finding proactive solutions to diversify the labour market, the Spanish government has so far been employing more and more public clerks, who do not necessarily benefit the Spanish economy in the long-term unless Spain’s economy becomes diversified. Indeed, enabling citizens to follow their own talents and dreams should be a part of Spain’s start-up strategy.

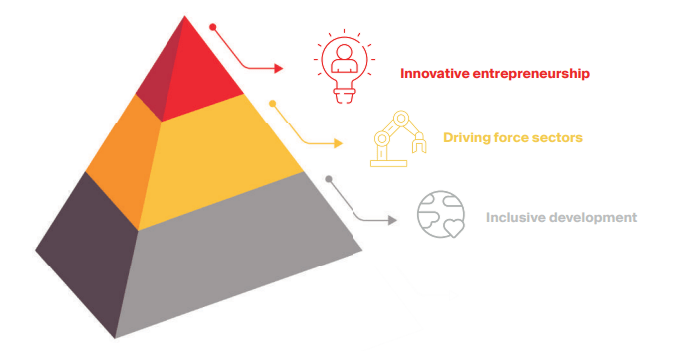

With tax hikes having led to miss prospects for a fast economic recovery after the COVID-19 pandemic, the Spanish government should thereby keep in mind that solving socio-economic issues, increasing labour market diversity and access as well as income equality should be the central goal of its Entrepreneurial Nation Strategy. The below shows Spain’s innovative entrepreneurship model, which is hoped to “increase economic productivity and generate quality employment for as many people as possible through the stimulus of innovative growth”.

While at first glance, the model seems to suggest that solving socio-economic issues as embedded in ‘inclusive development’ is already a priority of Spain’s start-up plan, this is a fallacy. As stated in the comprehensive document which explains the Entrepreneurial Nation Strategy, inclusive development is to be understood as the United Nations (UN) define it: “[It] can be achieved, by simply ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education, as well as promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all”. This definition reemphasizes that was argued above – even though the Spanish government claims that efforts to promote entrepreneurship education aim at making a start-up nation, it has not aligned efforts to reward young and trained entrepreneurs through diverse, realistic and scalable support schemes, which could meet the needs of different types of entrepreneurs.

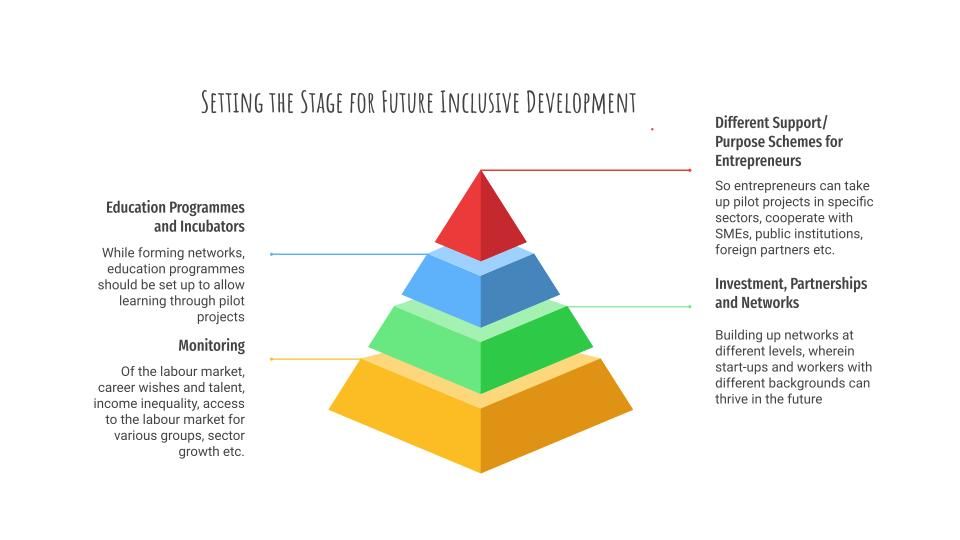

The above model is far from comprehensive, but suggests that inclusive development could be part of the vision, respectively the final goal of Spain’s start-up strategy. A few of the very first pillars to work on could relate to: 1) monitoring; 2) stimulating investment and building cross-sectoral, diverse (i.e. with schools, universities, SMEs, governments) partnerships at different levels (i.e. regional, interregional, national, international); 3) designing and executing education programmes in cooperation with incubators and other networks, which allow students to carry out pilot projects to actively contribute to innovation as well as normalize success/failure; 4) providing entrepreneurs with different support schemes with clear targets/purpose (i.e. pilot projects to stimulate knowledge creation and investment; sector-led projects; open-ended schemes etc.).

In a nutshell, the ‘Spanish Dream’ cannot be based on disproportionate risks, which individuals have to face while struggling to qualify as a ‘start-up’ anyways and get a rather poor opportunity for long-term growth and scalability. Instead, this dream must be based on building a system, where risk-taking can be limited to a reasonable amount. It is not only entrepreneurs who have to ‘learn’ the reality of the start-up scene, it is also this very scene which needs to be transformed by the efforts of the Spanish government. More than a dream, what Spain needs is a real transformation with a direct impact on career pathways.

Centurion Plus

Are you interested in starting or scaling up your business in Spain or another EU country such as Germany? Do you need legal advice to get a good assessment of whether your business plan is feasible? Then contact us today and don’t hesitate to let us know your perfect vision of a ‘start-up nation’.